In Conversation with Joy BC and Olivia Rose

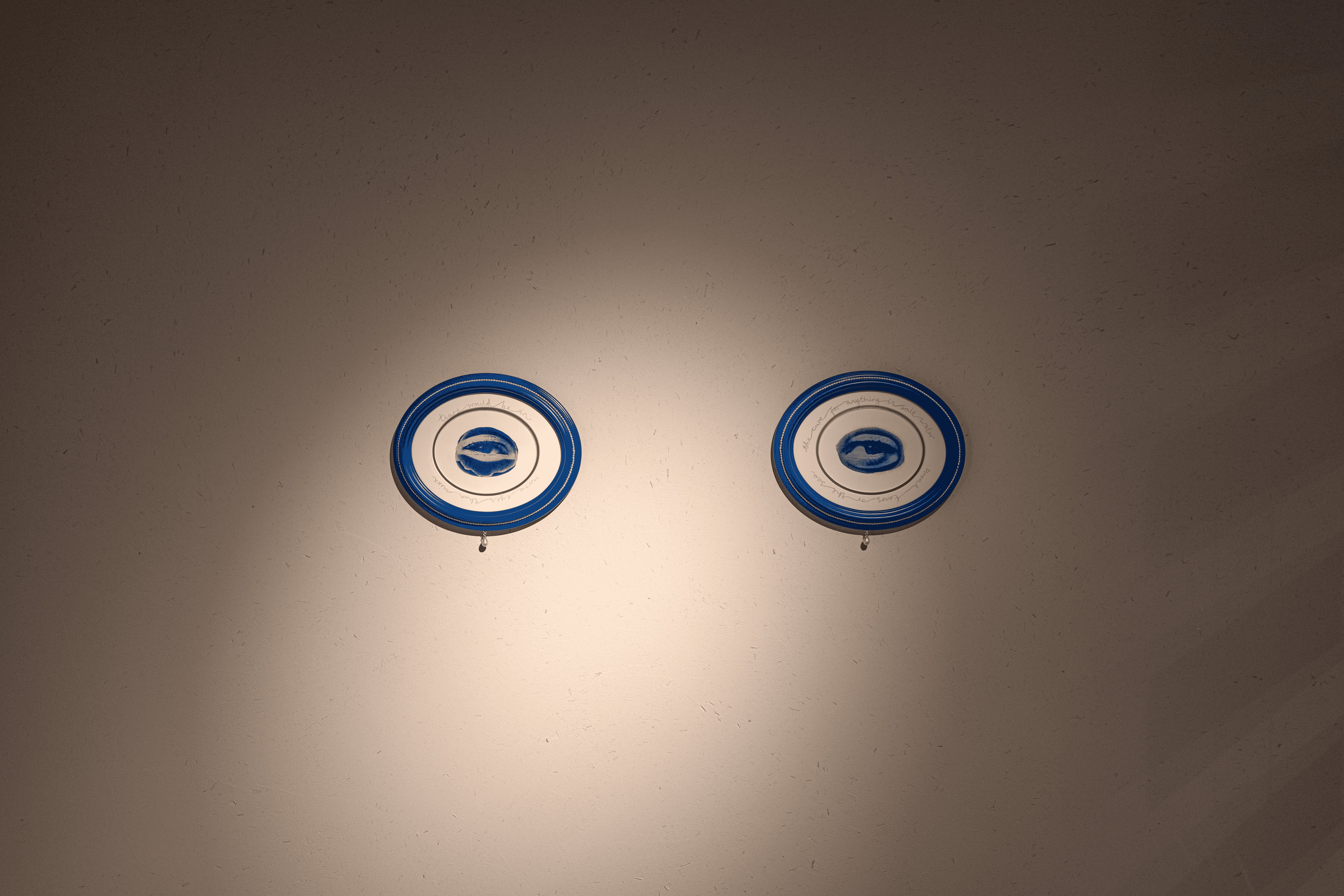

Lovers Eye is an exhibition presented at KG+ 2024 by British goldsmith and artist, Joy BC and British analogue photographer, Olivia Rose. Taking by the same title, the artists explore the 18th-century jewellery craze with multimedia artwork, from cyanotype hand prints, bronze brooch to video of the iris. The eye miniatures are shared between two lovers as an affectionate behaviour; the artists explore the history behind and the visual culture in today's world.

THE SHOPHOUSE: Research takes up a major part of your creative process; what have you found interesting related to these intimate objects in vogue in the 18th century?

Joy BC: The concept of Lovers eye came from an 18th-century craze in eye miniatures which were exchanged by lovers. You can imagine these were small pieces of jewellery which were either necklaces, rings, or brooches. They were a single eye, sometimes a double like a gaze, a section of someone's face looking outwards or to the side. They were surrounded by gemstones or pearls. This brief anomaly went between 1790 and 1820, it was quite a small period in which there was this craze around this exchange of this jewel, and the pieces were meant to be a reflection of a person's most inner, intimate thoughts and reflections, and often the eye is referred to as the window of a person's soul. That eye portrait could be worn publicly by the individual, the recipient of the eye, but was only recognisable between those two people. So no one else would know. Even though you were wearing this very intimate, personal portrait, it was only you who knew, who that individual was.

The lover's eye was used as a sound board or a starting point, and I loved the visual references of the singular, isolated body parts of the eye framed by the jewel. So rather than taking specifics or narratives from these pieces and their lives, we wanted to look at the eye as the main source of our research. Within that, we found lots of really fascinating facts. For example, blue eyes only existed from about 1000 years ago and can all be traced back to a specific gene. And that blue eyes, the actual pigment in a blue eye don't exist, it's the reflection of the light in the iris that we see this blue. Blue has been an emphasis within Western eye miniatures, and blue eyes have been represented a lot within jewellery.

We were more interested in looking at other eye colors such as brown greens and mottled tones. However, blue is an overarching theme within the whole of the show because of this feeling of illusion and also the way that Olivia has used cyanotypes, so this is our contemporary take on the lover's eye. For me, one of the things that was important in my research was looking at the gaze. And looking at the gender terms of the female and male gaze, the gaze pieces that I've done are non-gender specific. It's about how we look out into the world and if we consider how we look at things and conscientiously look at things, that we receive joy and love. So the lover's eye is about how we look. It's about ways of seeing.

Olivia Rose: Both Joy and myself came at this initial concept from different points of view, with Joy taking a more outward looking approach. For me, Lovers Eye was an opportunity to be introspective, looking at my own lovers and how they reflect upon me as an artist. What really interested me about the 18th century concept, was the idea that these jewellery pieces could be both simultaneously private and public; this is something that I have kept in mind whilst creating this body of work.

THE SHOPHOUSE: Can you talk about the beginning of your collaboration with each other?

Joy BC: Some years ago, Olivia took my portrait and we were in a graveyard in Ladywell, near where I live in South East London. When I saw the image, I felt that she'd captured me in a way that no one else had before. There was such strength and presence, and a way that I recognise myself when I look at myself, but I'd never seen anyone else capture me in a portrait before. As a sculptress, I have always loved drawing people, whether that's on buses, or in a park, from films, photographs, portrait drawings or something I've always done. And when I saw Olivia's portraits, there was something in her portraiture that I felt was real and that people were looking through the lens straight at you. I find that rare within. Well, it's just rare. I find it very beautiful.

Before I saw Olivia's work, she had asked me whether I would make her a Medusa ring. At the time, I was studying at the Royal College of Art doing my Masters, and I was researching Medusa. I was making a body of work which was a contemporary manifestation of Medusa as a series of bronze combs which are morphing and metamorphising, so she had asked me if I would do a classical ring of a portrait of Medusa. And I said ‘’Yes!" I think this is perfect for you because you're a photographer and you immortalise people. You capture people in a moment and famously Medusa turns her subjects to stone. It's a much better ending for her subjects, but there is this aspect of immortalisation within images, and I make all of my works. I often make pieces as markers in their lives at specific times.

So it felt really special to make this piece for Olivia. And she had said “This is the most important piece I've ever made for myself. This is really special.” And that's where our relationship began, so there was a really honest feeling between the two of us and about our work. That has continued throughout the years, and last year I did my first solo exhibition in New York, and I wanted to capture the pieces that I was going to be exhibiting there. Olivia and I started talking about it and we did a series of images of painted body parts, and isolated body parts. They were really beautiful and were all captured on film. Her ability to use film and analogue photography is very beautiful. THE SHOPHOUSE approached me and asked if I had this idea about photo collaboration sort of something I wanted to work on. I had this idea of the lover’s eye floating in my mind for many years, and it felt like the right moment and the right person that I wanted to work with. When I approached Olivia about it, she thought it was fascinating and both sides are deep-diving into the research.

Olivia Rose: Joy BC and I met when I went to her studio many years ago to commission a piece. Ironically, I had just had a very difficult break up and wanted Joy to create a wearable artwork that could remind me of my own power beyond the relationship. Unintentionally however, I ended up commissioning a signet that in so many ways, was related to the lover I had just lost, rather than being about my power as an independent woman.

This led to me asking Joy to consider making a Medusa ring - which at first, she vehemently opposed (it’s such a well known and overused symbol) until we started researching and decided that Medusa’s true story as ‘the women scorned’ was in line with the meaning I wanted Joy to infuse in the piece. Nine months later, my Medusa ring was born. And seven years after receiving her, she has literally never left my finger.

Joy and I naturally remained friends, geeking out together over fine art and conceptual thinking-spending time in the studio together (our studio lates!) and becoming artistic comrades, with similar focus for our work and similar values in life. Having collaborated before, we are constantly looking for opportunities to bring our differing skills together and the Lovers Eye body of work is an amalgamation of this.

THE SHOPHOUSE: Precious metals, mixed media installation, photography and videos, and the array of artworks showcase how seeing can be done in many ways; How do your skills and knowledge influence your “ways of seeing”? How does it come into play when working with the other artist coming from a different field?

Joy BC: I believe that seeing is not just with your eyes. So much emphasis is put on visual culture and how we look at things or how we're receiving things through a visual aspect. But I believe that your hands, heart and head are all connected. So when I’m using my eyes, I'm also feeling my way through things. The first sense we learn through is touch, and we touch our phones every day. We are gazing into these portals, into other universes, but we don't think about how we touch each other, or the weights and feelings that we have through the tips of our fingers in that way I believe. I can see something and I think about how it feels, how I want to run my fingers across its edges, whether it's cool or warm to touch. I don't just think visually when I'm thinking about seeing, I think about how it feels, how its weight and how its presence is.

And working with Olivia, I feel that we've been challenging some of the ways of seeing how we look at things with photography, how it's covered by glass, protected, or with the formalities of how we present prints and look at things, so using smashed glass, combining these multimedia pieces, putting the emulsion directly on the glass, printing onto the glass, drilling the glass, and then holding the glass together with metal, staples combining different materials. They're not necessarily things that you would put together instinctually.

In the same way as adding a diamond to something like a smashed piece of glass, something that has fragility and yet connotations of something being everlasting or immortal, I constantly think and look through my hands and I hope that that's also projected within the work we've taken physical. Pieces that are worn on the body and projected back through a camera. Onto an image of which we've directed, which then have come back. There's a lot of back and forth between different realities, the physical, the analogue, the digital and the tactile.

Olivia Rose: Ways of seeing are integral to all artistic endeavours! Our unique perspectives, formed by our gender, culture, sexuality, geography, religion, race and place in society, ultimately effect how we look at everything in the world. And in turn, these unique perspectives are what influence our creative choices; both how we view artworks and how we interpret concepts and ideas in order to respond with unique works.

I am often asked by younger photographers “what camera do you shoot on?” Or “what lens do you use” - and I always respond telling them that they are asking the wrong question! Because it’s not the technology or equipment, but the eye of the artist, that creates a unique final image. It’s when we decide to hit the shutter release, how we got on with the person before we took the portrait, how we frame the image etc that really make one photographers work distinct from another.

For this body of work, Joy’s skills as a goldsmith - the very nature of her working with her hands - really inspired me to go back to my craft roots. I am a maker - it’s the reason I am so hesitant to work with digital methods, they don’t contain the alchemy of the lab, nor the beautiful imperfection and prolonged experience of film. It’s a rare medium in today’s climate that doesn’t garner “instant” results and this is crucial to my practice.

The alchemy involved in my home darkroom process of creating cyanotypes spoke so clearly to the processes Joy uses as a jewellery maker and this helped us to see the work as a cohesive body with a united vision.

THE SHOPHOUSE: There are many site-specific artworks in Lovers eye, would you like to share one of them with us?

Olivia Rose: Almost all of the artworks for Lovers Eye were made specifically for the exhibition itself. I think for both myself and Joy BC, this body of work was an opportunity to push ourselves in different directions and for me this meant advancing my personal involvement in my own practice - moving from a commercial dark room to a home dark room in order to coat papers and make cyanotype prints from some new and old portraits.

Similarly, it opened a space for me artistically to return to making. The Broken Gaze pieces for example, are an expansion on my experiments with glass printing. Before Lovers Eye these didn’t necessarily have a place in my portfolio, beyond tests. It was in reacting to our concept that the idea of smashing the photographic glass prints really came to life - a physical manifestation of the broken lovers gaze. This type of work thrills me and I hope to continue making in this way moving forward.

Joy BC: The cure for anything is salt water, sweat, tears, or the sea. This is a quote from Isaac Dennison, who wrote Babette's Feast. It's something that a friend said to me many years ago, and it's my favorite quote of all time, and I really believe it.

THE SHOPHOUSE: A normal portrait would show the whole face or body, disclosing more details and signs, of the person. How do you feel working with just the eyes of a person on this project? And how is it different from your usual portrait practice?

Olivia Rose: Working with just the eyes of a person has been such an interesting advancement of my understanding of a portrait. By isolating one body part, I am immediately playing on the private or public nature of the work. Is the person still identifiable? Perhaps only to themselves and those that know them closest?

The eyes have long been described as windows to the soul and I found this to be true during the process of making the portraits; it is a particularly intimate experience to just photograph an eye. You physically have to be closer to your subject - focusing is harder - getting them to have the right look is a matter of micro movements rather than larger gestures. This tested my skills - but allowed me to expand my idea of a portrait.

THE SHOPHOUSE: I personally find your photography works masculine and sometimes confronting. In one of the interviews you also mentioned that your works are "Masculinity reinterpreted via feminine gaze". In Lovers Eye, you seem to take on a more feminine approach with the incorporation of mixed media, such as, hand-printed cyanotypes, hand stained woods and human hair. Would you like to share with us on that?

Olivia Rose: This question is both confronting and revealing for me; you may have inadvertently hit upon a deeply psychological idea that I have been grappling with as a person and in turn an artist.

I think I have been a person who was shaped by a need to adopt the more powerful traits of masculinity and I think to date this has really influenced my way of seeing. It also influenced how I would interact with my sitters; I am confident, direct, funny - at times a little outrageous and daring, all qualities traditionally associated with the masculine. But over the years I have been in therapy, working on myself from a very introspective place. This has in many ways allowed me to feel more confident within who I am at my core; a sensitive, feminine, emotional being. I think this has encouraged me to soften my practice - to appreciate more the methods of working that I employed in this series, which were often more solitary, alchemic and experimental than my usual way of seeing.

I think in many ways this has allowed me to be more open with my own truths and that’s reflected in the Aphrodisiac piece, which is deeply personal to me and is infused with details that nod to the lover on whom it is based. The red hair is representative of me. The hand stained wood is a skill I was taught by him. The images used in the piece are a symbolic amalgamation of us both.

I am proud that this femininity is showing up in the final work. I hope I can continue blending these aspects of myself moving forward.